It’s the standard traffic for a Wednesday afternoon in the West Baden Springs Hotel atrium. Tour groups milling through. Across the atrium, a few dozen folks enjoying afternoon tea with harp music wafting throughout. There’s first-time visitors simply staring at pointing at the dome overhead. Others have claimed a comfy chair and are licking ice cream cones.

In the middle of it all is Mary Lassiter. You could make the

case that her family is the reason we’re all here enjoying ourselves under the

dome.

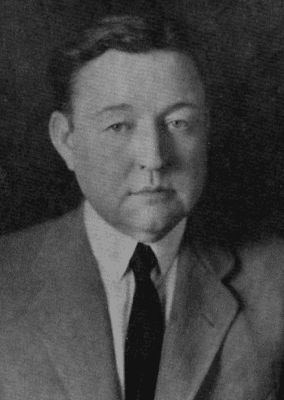

Mary’s great-grandfather was Ed Ballard, the man who owned

West Baden Springs Hotel from 1923-1932. Mary never met her grandmother (Ed’s

daughter). And Mary wishes we could’ve found out more tales about

great-granddad from her mother, who died about a year and a half ago and wasn’t

much of a storyteller in the first place.

But Mary’s heard bits and pieces about her

great-grandfather, his colorful life and his magnificent hotel — enough to make

her feel bonded to Ed Ballard when she sees old pictures of him.

“I’ve always felt sort of connected to him,” she says.

Mary has lived out West most of her life, currently in Salt

Lake City, and last week she was finally able to visit West Baden and see what

her great-grandfather once ran. And if it weren’t for Ed Ballard, West Baden

Springs Hotel might not be standing today.

Ballard took ownership of the hotel 22 years after it was

originally built, and after the Great Depression struck and his hotel business

went south, Ballard famously sold the building for $1 to the Jesuit Society

which operated its seminary there. The Jesuits inhabited the building through

the mid-1960s, then Northwood Institute used the building until the early

1980s.

By essentially donating his hotel to the Jesuits rather than

just letting it sit empty, he set forth a sequence where the building was

inhabited and maintained for the next 50 years. Considering how badly the

building deteriorated from 1983 to 1996 when the restoration process began — parts

of the hotel exterior were literally crumbling by then — it would’ve certainly

been in disrepair had it been vacant all those years.

And we have Ed Ballard to thank for that.

No surprise that Ballard made a sage decision there, given

that he was considered to be one of the most economically powerful people of

this area from 1910 through the 1930s. His interests covered everything from

farms to rental properties to circuses to banks.

His first job was being a pin setter at a bowling alley, and

then he delivered mail on horseback in the county’s rural areas. But Ballard

didn’t see a future delivering mail, so he made moves. Not long after his 21st

birthday, Ballard was running a tavern called the Dead Rat Saloon near West

Baden Springs Hotel that was frequented by guests since the hotel didn’t serve

alcohol. Ballard ran a couple saloons with both fun and games — he was also running a small gambling parlor in the

back. (This was all kept hush-hush, since Ed’s mother was a religious lady who

wouldn’t even allow her sons to bring a deck of cards into their home.)

Mary shares a tale she heard about Ed’s underground games: “He

ran a little card game, and there was a hardware store nearby. He would run to

the hardware store to borrow cash from the owner. He’d borrow this cash and

he’d always pay it back, but then one time he had a chance to do a bigger game

down the street and he needed $1,000. This hardware store owner loaned him the

money again. (In later years) when that man was going to go into bankruptcy or

having financial difficulties, Ed loaned him some money. When it was time for

the debt to come due, he essentially forgave a good portion of that debt,

because he always remembered how this hardware store owner loaned him money all

the time to run these card games. Basically, he was who he was because this

hardware store owner loaned him money all the time.”

|

| The West Baden Springs Hotel atrium, early 1900s. |

There’s also a famous tale about how Ed Ballard got on Lee

Sinclair’s radar as a young man. Sinclair was the one who built West Baden

Springs Hotel and owned it prior to Ballard. In those days, hotels had their

own ice houses where they’d cut ice from the rivers and ponds in the winters

and store it for later months. In the summer of 1895 (when Ballard had just

turned 21), Sinclair’s hotel ran out of ice. Sinclair sent a messenger across

the road looking for a favor, as Ballard had also built an ice house for his

saloon.

“Tell Colonel Sinclair

he can have anything I have,” goes the story. “Col. Sinclair never forgot this gesture.”

A few years later, Sinclair selected Ballard to run West

Baden Springs Hotel’s casino — that was in the day the hotel had a casino on

property. All these years later, it gives Mary a sense of wonder about how her

great-grandfather provided gambling and drinking to people in the era when it

was illegal: “I don’t mind that he was a little bit strategic. You have to be

able to appreciate a little bit of deviancy.” Especially since she’s heard

stories that suggest Ed Ballard had a truer moral compass than most business tycoons.

|

| Mary and Ethan outside the Ed Ballard room at the hotel. Mary's middle name is Elizabeth, which has been in the family for generations as Ed Ballard's mother and daughter were both named Mary Elizabeth. |

“He understood there would be a sense of ruin if the

townsfolk lost their money there,” Mary says.

Ed Ballard lived larger than life all the way to the day he

died — murdered in Arkansas hotel room in a dispute over a gambling club he

owned and later sold. His life and times are like something straight out of a

fiction novel. And almost a century after Ed Ballard ran West Baden Springs

Hotel, his great-granddaughter has a sense he’d love what it’s become today.

“We were sitting in the restaurant and I was watching the

folks coming and going thinking, people are employed here and this town has

some vibrancy because of this place. I just felt for a moment a sense of pride,

for him, if he could see this today. And what would it feel like to have him

standing there looking, saying, this is

awesome.”